We finally have an understanding of how Mars transformed from a once habitable, Earth-like planet into the dry world we see today. NASA researchers have just announced that Mars' once rich atmosphere was stripped away by solar winds in the early days of the Solar System, causing the planet to dry out.

Solar winds blast out from the Sun at around a million miles per hour (about 1.6 million km/h), and fortunately Earth is protected from these by our magnetic field. But although Mars used to have a magnetic field, it lost it as its planet cooled down billions of years ago, and that allowed the ions in its atmosphere to effectively be blown away.

Scientists were able to figure this out using the MAVEN (Mars, Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) spacecraft, which has been orbiting Mars since 2014. Last year, the probe was lucky enough to be able to observe the direct impact of a solar storm on Mars' atmosphere, and showed that the solar particles were energising the gases in the upper atmosphere, causing them to blast into space – and likely out of our Solar System.

You can see that happening below:

The measurements have also provided some insight into the gases that were lost from the Martian atmosphere, which include hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide – all things needed to create a habitable world.

And as far as we can tell, Mars really was oh-so habitable back in the day. NASA researchers believe that around 4.3 billion years ago, Mars had incredibly deep oceans that held more water than the Arctic Ocean here on Earth.

From this new research, it appears that Mars' oceans evaporated due to the planet's thinning atmosphere, and then slowly leaked out into space. The results have been published in four papers in Science (here, here, here, and here).

Read live updates from the NASA briefing below:

6.02am AEST: OK here we go guys, it's live! "Maven is helping answer a question scientists have been asking for decades: Where did Mars' atmosphere and water go, and could the same thing happen to Earth?"

6.03am AEST: Water, we're going to be talking about what what happened to the water. Yes!

6.05am AEST: Maven is a "mission that's been under budget, on time and performing beautifully," says Michael Meyer, lead scientist for the Mars Exploration Program. And he tells us: "The answer [to where the water went], my friend, is blowing in the wind". (Side note: we love scientists quoting Bob Dylan).

6.07am AEST: For those playing along at home, MAVEN scientists have released four papers in Science today which describe their first findings. We'll be getting into them in more detail, but for now you can read the abstracts here, here, here, and here.

6.08am AEST: So we now know that the solar wind has played a big role in stripping Mars of its atmosphere. The solar wind blasts out from the Sun at around a million miles an hour, and can grab ions from a planet and strip them away. This is what seems to have happened to the gas in the Martian atmosphere.

6.09am AEST: Earth is protected from the solar wind thanks to our magnetic field, which Mars doesn't have. Thankfully the Martian atmosphere is still strong enough to stop the solar wind from hitting the surface of Mars, which is a good thing for future missions and colonists. Instead, the solar wind is deflected around the planet.

6.15am AEST: We've got lots of details coming at us, which we'll summarise for you properly in a few minutes. But first, some graphics.

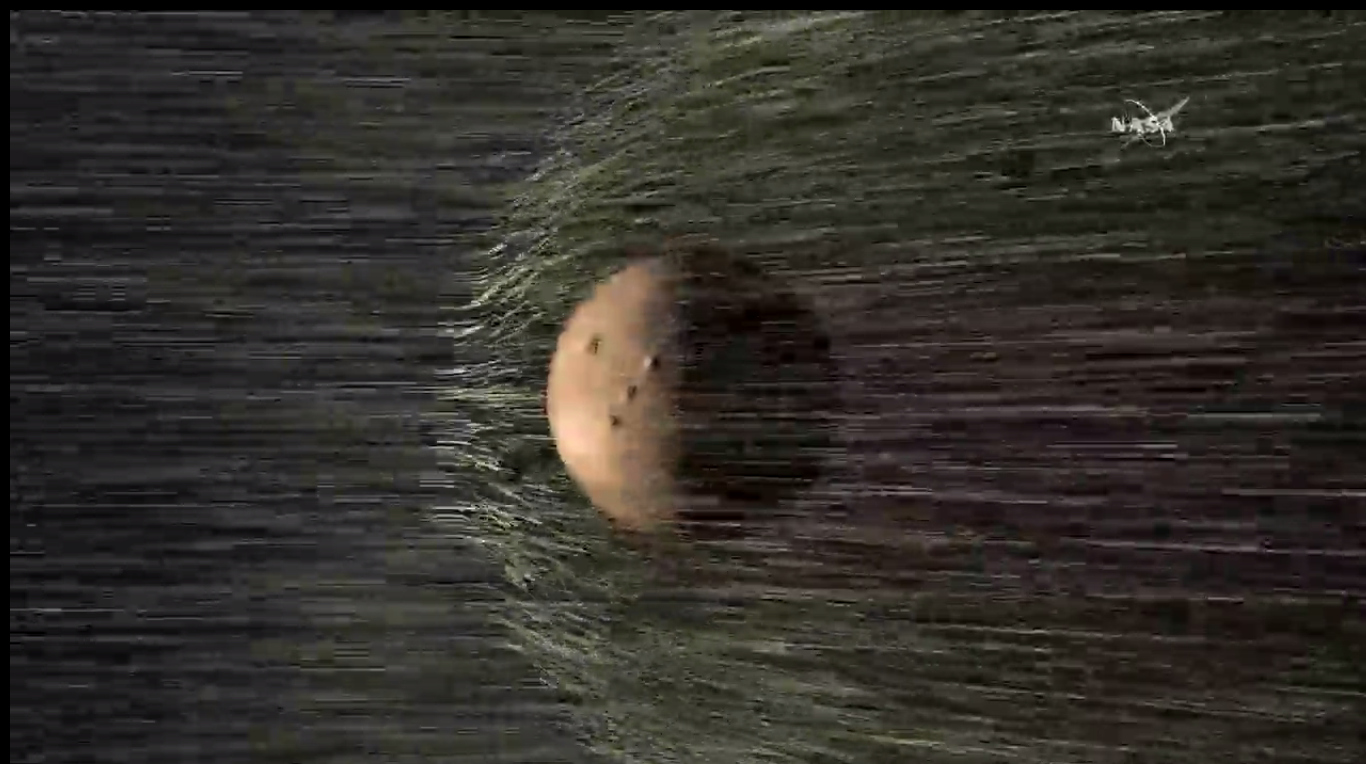

Here's the solar wind hitting Mars:

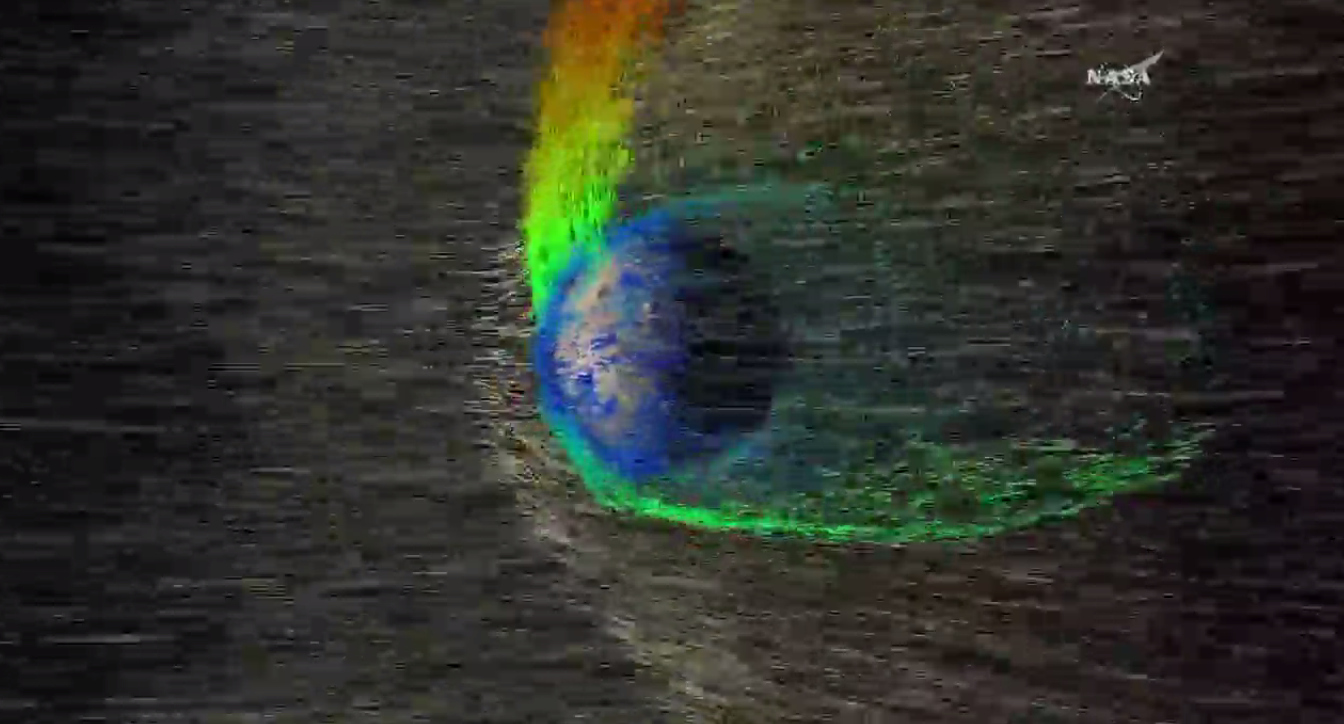

Here are the ions escaping from the Martian atmosphere, as they're knocked away by the solar winds:

6.19am AEST: Scientists have been able to map out how much of Mars' atmosphere is being lost all the time, and it's around 100 grams of atmosphere escaping every second. Adorably, they compare this to a hamburger escaping every second. But it's not hamburgers, it's oxygen and carbon dioxide, which are important both for water and for the climate of the planet overall.

6.21am AEST: Last year, MAVEN was able to detect that the escape of atmospheric particles goes up by a factor of 10 or 20 when there are relatively weak solar storms. Given that there were more solar storms early on in the formation of the Solar System, this suggests that a lot of the Martian atmosphere was lost early on.

6.22am AEST: Oh Dwayne, we all have a craving for hamburgers now.

6.23am AEST: It's crazy to think that these results are all from the first six months of MAVEN's data. We can't wait to find out more!

6.24am AEST: Good question: "Is the same thing happening to Earth, or could it happen in the future?" And slightly worryingly, the answer is yes: Earth is losing atmospheric particles all the time. But we do have a big magnetic field that shields us from brunt of the solar winds, so we don't need to panic until we lose that magnetic field (which could happen when the planet's core cools down).

6.28am AEST: Great ELI5 metaphor here from Bruce Jakosky, the MAVEN principal investigator: Think of Mars' atmosphere just like the water on your hair when you step out of a shower into a breeze – it all just gets blown away.

6.32am AEST: Lots of great questions. Our favourite: Is it possible to reverse the effect of this atmosphere loss? And bad news for all you terraforming buffs out there - the answer is no. As Bruce Jakosky explains, it would be possible if the CO2 lost from the atmosphere had been locked up in Mars' crust, but instead it was stripped away into space and by now has been removed from the Solar System entirely.

6.38am AEST: Why is all this important? Great answer from Jakosky, who says that it all comes down to our understanding and search for life outside of Earth. From everything we've learnt so far, the Red Planet met all of the conditions for life at one point in time. "So it begs the question of whether there ever was any life there," explains Jakosky. "As we go into the future, these question about life and climate and the history of the planet as a whole really are at the centre of exploration."

6.42am AEST: Great description of the new kind of aurora observed at Mars – an aurora that occurs in parts of the atmosphere that aren't above magnetic fields. We want to see it!

6.52am AEST: OK guys, it looks like things are getting wrapped up. Thank you for watching with us! We'll be updating the story above to make it a more coherent summary of the results, so stay tuned. And huge congratulations to the MAVEN team!

Background:

It's time for round three (or is it 37?) of the NASA big announcement game. This time the topic in question is the Red Planet's atmosphere and more specifically, what the hell happened to it. The live briefing above starts at 2pm EST on Thursday 5 November (7pm UTC and 6am AEST Friday), and we're going to be updating live below with the latest findings. But before we do, here are some things we know so far.

First of all, we know NASA is about to release the first findings from the MAVEN mission, which stands for Mars, Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution. And we know that we're about to find out some of the backstory of what happened to Mars' atmosphere.

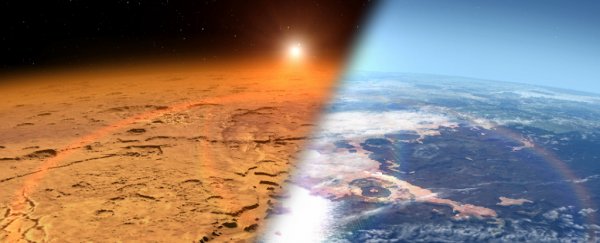

Right now, Mars' atmosphere is thin and bone dry, but scientists think it wasn't always that way. This NASA-created Vine below shows a recreation of what Mars may have once looked like… which, interestingly, looks a lot like Earth.

Why is Mars' atmosphere important?

Why do we need to know what happened to Mars' atmosphere? Because once we understand that, we'll be able to work out what happened to water on the Red Planet, and it could also hold clues as to the habitability of Mars in the future. Not to mention the findings might prove crucial to NASA's mission to Mars (which it's currently recruiting for, just FYI).

NASA dropped a big clue on Twitter that the findings may have something to do with the solar wind.

‘Gone with the Solar Wind’: Watch live at 2pm ET for a new #MarsAnnouncement. Qs? #askNASA https://t.co/KX5g7zfYQehttps://t.co/81ChANXqH7

— NASA (@NASA) November 5, 2015

We're hoping this means we might also find out something about the mysterious, super-powerful aurora spotted earlier this year on Mars.

Either way, we're excited. So settle in with some popcorn (or if, like us, it's 6am where you are, maybe a strong coffee) and watch as we finally find out the story of Mars' atmosphere. Ask your questions on Twitter via #askNASA.